Tribute to Aloha Wanderwell-First woman to travel around the world.

- The Mysterious Aloha Wanderwell

- Aloha Wanderwell Global Expedtion Timeline

- Adventures with Car & Camera

- When Travel Was Adventure

- Aloha Wanderwell Movies

- Aloha Wanderwell Galleries

- The Story of a World Traveler

- True Tales of the Wanderwell Expedition

- Call to Adventure

- Wanderwell Expedition

- Aloha Wanderwell official website

The Mysterious Aloha Wanderwell

Aloha wrote Call to Adventure in 1939 at the age of thirty-three, a compendium of her groundbreaking forays into the unknown that sealed her status as the “Amelia Earhart of the automobile.” However by this time she had also been christened the “Rhinestone Widow” by the press, as her business partner and husband Walter Wanderwell was mysteriously shot and killed aboard their boat harbored in Long Beach in 1932. Aloha’s detached reaction to his death, as well as her subsequent marriage to cameraman Walter Baker (eight years her junior), were found suspect and a bit malevolent by media observers, and a pall hung around her carefully crafted image.

Aloha wrote Call to Adventure in 1939 at the age of thirty-three, a compendium of her groundbreaking forays into the unknown that sealed her status as the “Amelia Earhart of the automobile.” However by this time she had also been christened the “Rhinestone Widow” by the press, as her business partner and husband Walter Wanderwell was mysteriously shot and killed aboard their boat harbored in Long Beach in 1932. Aloha’s detached reaction to his death, as well as her subsequent marriage to cameraman Walter Baker (eight years her junior), were found suspect and a bit malevolent by media observers, and a pall hung around her carefully crafted image.

Call to Adventure, as well as a radio show, were amongst Aloha’s efforts to rebrand herself. Aloha was emblematic of the 1920s, the decade she hit the world stage, but she was also a complete anomaly, making her story all the more fascinating and inscrutable.

Aloha came of age in the wake of WWI, the bloodiest war the earth had seen. Nine million people were killed. Trench warfare took military technology to new heights; tanks, poison gas, and machine guns forged unheard-of death tolls. Countless families lost fathers and sons. Survivors of the war returned to their families physically and psychologically brutalized. Europe and America were enveloped in a post-traumatic malaise that challenged assumptions about faith, the future, and daily life that shook a generation to its core.

This deep collective despair found its relief in the expansiveness and almost over-the-top optimism of the twenties. The United States, Canada and Europe became cultures populated by what Joseph Campbell called “fatherless heroes”: men and women who, without the love and safety of a paternal figure, re-imagined themselves as “citizens of the world”. Not unlike the genesis of the super hero, an entire generation was robbed of its traditional familial roots, engendering a sensibility of deep ennui and loss, but also limitless possibility and a drive to break old paradigms. This new generation was going to make sure the worst would never happen again—the twenties would be their revenge and redemption.

Smashing of limitations could be seen in the huge strides made in technology and infrastructure. Electricity became commonplace in American homes. Skyscrapers began to loom upon the American skyline. Politics took on a globalist tinge. Madison Avenue and commercial marketing, brought to you by way of radio, urged the consumer to live the dream. The availability of credit, and the “buy now pay later” philosophy touted on the airwaves gave way to a sense of power and instant gratification that was to become a distinct part of the American character.

It was also the Decade of the Car. The horse and buggy were made obsolete by paved roads and the Model T Ford, the first vehicle common folk could afford. Adventure and leisure were not just possessions of the elite; now even the middle class could get a piece of the action.

As the war brought seismic shifts in the traditional family structure and assumptions on how life “should be”, it also brought women into a more central cultural role as actor rather than observer. After much struggle, the Women’s Suffrage movement got women the right to vote. Technological advances like the dishwasher and the washing machine helped the homemaker multi-task in unheard of ways. She was no longer just a spouse, she could now be a “super wife”.

At the center of the culture war was the ubiquitous flapper. With bobbed hair and heavy make up, she was a product of the new transatlantic sensibility that had taken hold. She was sexually liberated, licensed to drive, and she smoked in public as an act of flagrant rebellion. Marketing was already placing its stamp on youth culture. Cigarettes, once associated with prostitutes, became “torches of freedom” in the hands of public relations mastermind Edward Bernays. Jazz, a new form that brought a monolithic vitality to music and art through improvisation and the mixing of black and European musical traditions, was the flapper’s music.

The arts were galvanized by writers like Colette, who spoke frankly about female experience and sexuality in ways that would be previously considered scandalous and perhaps criminal. Her breakthrough 1920 book, Cheri, tells the story of a romantic relationship between a middle-aged courtesan and her young male muse, Cheri, whom she pampers and dresses in silk pajamas and her pearls. It is no coincidence that Aloha, who could have been a creation of Colette herself, quotes the author in the first paragraph of her second book The Driving Passion: “Though the ever-vigilant attachment remained, the child savoured life with an independence much greater than that allowable most French children….”

Aloha was born Idris Galcia Hall on October 13, 1906 in Canada, the daughter of a British Army Reservist. In Call to Adventure, Aloha depicts a laughter- and love-filled childhood set in a log-compound that inhabited forty acres of lush Vancouver wilderness at the water’s edge. The Halls’ lifestyle was decidedly unorthodox: They had a chauffeur and a cook, and their own yacht, but the family also swam together in shallows, climbed trees, and lived off the fat of the land. As Aloha tells it, their life was a wilderness vacation for wealthy folk.

Aloha herself seems a perfect hybrid of her parents. She describes her mother as a “matriarchal Victorian seeking new creative life-style for women”, which could have been a description of Aloha herself. Her father’s credo was, “England expects every man to do his duty…keep a stiff upper lip.” In Call to Adventure, her observations are often breathlessly descriptive, but not at all emotional. She retains a can-do attitude and candid detachment throughout that comes from life experience beyond her years and an admiration for hard work and sticktoitiveness. She expresses her sexual curiosity and appetite in a thoroughly modern manner, but she frowns upon drinking, smoking or anything remotely “vulgar”.

Idris was brought into the cruelties of reality in 1917 when her father was killed in action in Ypres. This trauma helped to mold the woman and the mover and shaker she was to become. Already a tomboy, the death of her father gave rise to her urgent need to become the man of the family. Someone had to be the familial protector, and money and career became a prime concern. Like others of her generation, almost unwittingly, Aloha was thinking in novel and inventive ways about how to live her life. And unlike most other girls, she had the drive, stamina, and stature to live that life.

Her mother enrolled her in a stuffy and restrictive French convent where she became something of a troublemaker amongst the severe and sometimes abusive nuns. She insisted on certain liberties like having her own room with an open window to allow the breeze in. She was outspoken and would defend the underdog in class situations, even to her own detriment.

Aloha found solace and connection with her father in his boyhood books like The Three Midshipmen, which were filled with tales of swashbuckling high adventure. She also read romantic paperback novels that told tales of equally nervy heroines. The imprisonment in the convent, the dreary and foreboding post-war landscape, and the unrealized wanderlust in her now sick mother seemed to supercharge her restlessness. Like many young people of the 1920s, she felt a sense of her own limitlessness, and an ill-defined entrepreneurial impulse that craved expression: “What those heroines did! What narrow escapes they had, and how I longed to become one of them! I had a certain facility for doing things; languages were mine without great effort. I was at home in French as in my native tongue. Spanish, German, and even a working knowledge of Italian were acquired with no hard study. I could ride, swim, dance. “

Aloha was also inordinately tall, making her something of an alien. She grew to be six feet in stature, when the median height for women at the time was 5’2”. The difficulty in finding clothes, shoes, and a feeling of physical normalcy amongst her peers must have been extremely daunting. With her rare movie star visage, blonde hair and robust stature, she had to have been a target, even on a subconscious level, by those around her—a veritable freak. Aloha never mentions any such phenomenon, and never makes any issue of it in the book. Her height may have aided a feeling of deep difference or insecurity that could have spurred her to achieve more than the women around her. It certainly enabled her to be the absolutely formidable presence she was in situations on the road that would have toppled most women.

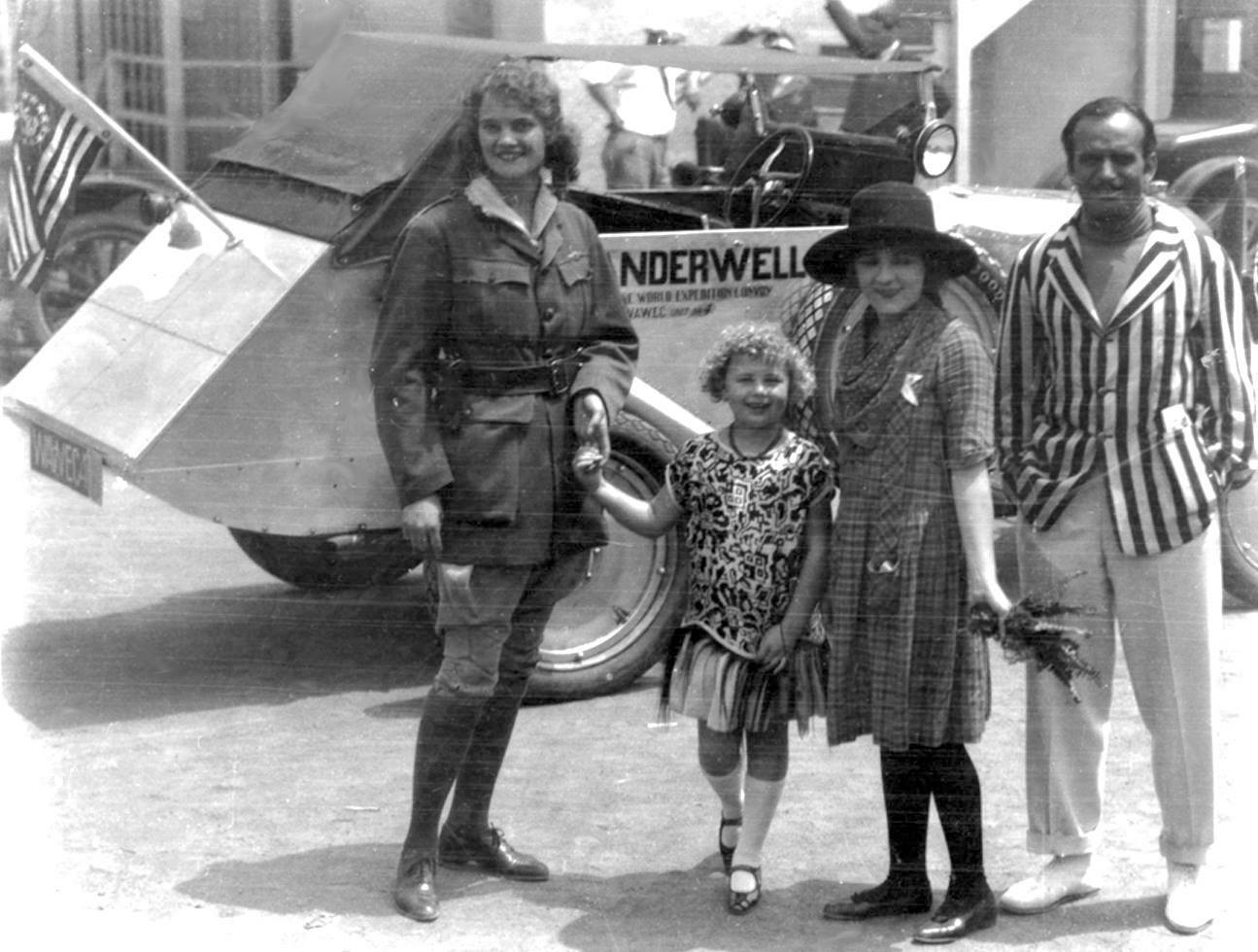

As in many tales for young people, Aloha’s pivotal moment occurred at the age of sixteen. The Paris Heraldcontained a want ad: “Brains, Beauty & Breeches—World Tour Offer For Lucky Young Woman…. Wanted to join an expedition…Asia, Africa….” Fate brought her into the environs of the equally restless Walter Wanderwell, a Polish émigré who had reinvented himself as an Anglo explorer. Polish by birth, but definitely American in his thirst for thrills, influence, and globalism, his passion above all was world peace and the formation of a world armament police. Wanderwell had obviously been deeply shaken by World War I and wanted to make a difference. He needed a female secretary and companion to film and star in his expedition-by-car around the world. This expedition would be both a vehicle for his exploits and his pacifist cause. It would take a rare woman to match the grandeur of this enterprise, and Aloha was that woman.

Like Aloha, Walter Wanderwell was a paradoxical and enigmatic figure. His yearning was vast, perhaps excessive, and his stamina seemingly endless to achieve his goals, but like Aloha, he eschewed the customary partying and carousing of the period. He was a mystic and deeply spiritual. In terms of lifestyle, he was Spartan and ascetic, but not in his predilection for women.

When Aloha’s adventures began, there were other female explorers in the public eye, but none had the sheer scope of hands-on achievement, and the downright earthiness that Aloha possessed. Amelia Earhart flew high in the sky and was supported by an advertising team and corporate funding. Aloha was a creature of the celebrated automobile, and she extrapolated wildly on the adventure it offered. With pet monkey Chango in tow, the Wanderwells drove through dust, mud, and rain, and the fate of their journeys often lay in the hands of the people they encountered on the road. They were creatures of the moment, and though they were often feted by noblemen and royalty, they also slept in vermin-ridden huts and fought off starvation and illness. All of this, for Walter, was done in the name of world peace. For Aloha, it was the “ravishing thrill”.

There is indeed a David Lean-esque scope to the tales told in Call to Adventure, and also a comic-book sense of constant dances with injury or death. Dressed in utilitarian breeches and flying helmet, Aloha makes her first perilous trip en route to meeting Walter in France on a boat where woman are not usually allowed to travel. She fights off rank smells, cold, and rape. Aloha almost dies from a mosquito bite in one sequence and from exhaustion and hunger in another. She regales the reader with a suspenseful and morbid account of funeral rites in Bombay at the Tower of Silence, watching carrion birds fly overhead. In a sequence befitting George Lucas, Aloha enters the inner sanctum of Mecca, going where no woman ever in human history has gone before, and she enters with little trepidation or doubt. She presents a quality that we see over and over in this heroine: She never ever asks permission for anything.

The Wanderwells were DIY. They funded every foot of their travels through Europe, Asia, Africa and South America with shows for the general public, featuring films they had shot of the location and milieu they had encountered before. In Call to Adventure we are treated to a vast array of colors and sounds. They managed to capture worlds of human existence never before recorded. Some of these worlds, tragically for us, no longer exist. They do exist however in the 1929 documentary With Car and Camera Around the World, which made them internationally acclaimed explorers.

Aloha was not only the blonde star of these films, she also stood behind the camera and called the shots. She held the nitrate film in her hands and acted as editor along with her husband. By necessity, Aloha was once again smashing customary limitations and boundaries for women.

Mysterious Sensation

Adored and scrutinized by the press, Aloha became intoxicated early on by the attention and fascination complete strangers held for her. She was an extremely adept and entertaining storyteller, and her legend drew big crowds to their presentations. This admiration became part of her “ravishing thrill”, and another source of adrenaline and sensation, which Aloha needed and craved, and enabled for the rest of her life.

Even in motherhood, Aloha could not summon the will to curb her wanderlust. She describes giving birth to both of her babies, honestly expresses her perplexity at motherhood, and unapologetically leaves them in the hands of caretakers to continue her adventures on the road. From the pen of a man this would seem unfortunately customary; from a woman, it is jarring and somewhat controversial.

Her view of other people and other cultures, though completely of her time, are not always pleasant to read. While the 1920s was an era of ideological and technological growth, American exceptionalism and racism were still the order of the day for the majority of white people. In most of her accounts, Aloha retains the haughty distance of a missionary and an imperialist. Never at any time is that wall penetrated, no matter the beauty or the courageous character of the cultures that either welcome her or look on her with perplexity, and sometimes derision.

Something of an exotic at home, Aloha continued to be anomalous in far off climes. Perhaps she liked it that way. Perhaps there was some safety in being a perpetual stranger. She writes about her travels in Egypt: “Peasant women trailed black skirts in the dust, and their chains of barbaric jewelry swung and clinked with each step. I had a queer feeling of kinship, a feeling which comes back to me over and over when I set foot in the strange, out-of-the-way places of the world. “

In the unique blend of legend and biography that is Call To Adventure, whether standing amongst the bitterly oppressed Pashar women, or the genteel British transplants in India living a Western life in an Eastern culture, Aloha is always a visitor at arm’s lengths with everyone around her. It is this sense that she retains even to the reader, a heroine who flashes brilliantly across the mind’s screen, who every thirty seconds achieves some impossible act, but will never really let us close, who will never really let us in.

Credits: https://www.alohawanderwell.com/